Liszt the Teacher

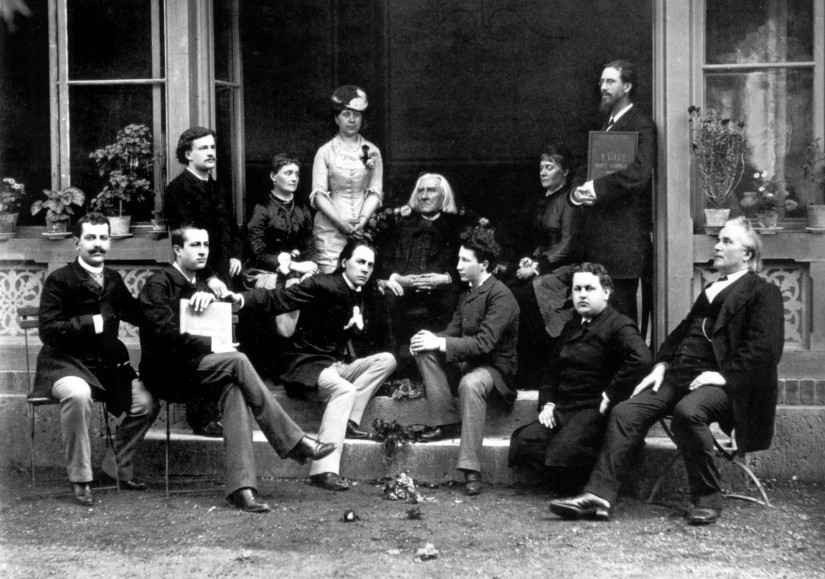

The exhibition Liszt the Teacher aimed to present Liszt’s exceptionally broad mentality and artistic approach — qualities that, even at an early age, manifested a clear commitment to sharing universal education.

During his career as a teacher he practically realised or sought to achieve these aims, which he had written in 1835 (On the position of artists and their place in society). His essay mentioned the creation of a new music collection of his most outstanding contemporary works, and a music library spanning the period of music history from the Renaissance to the music of his time. This collection of music, which he called The Pantheon of Music, would have been enriched by essays, biographies and commentaries on the works, thus creating, together with the music, a veritable musical encyclopaedia. He wanted to make the publications widely available in cheap editions, as well as to introduce music education in folk schools and other schools. To ensure this goals, he wished to organise higher musical education, not only in the centres, but also in country towns, under the leadership of the most eminent artists. He also wanted to establish a department of philosophy and music history as part of higher music education. He called for the creation of choirs in churches to perform sacred music from the Gregorian chant onwards, and for a reform of the performance of Gregorian chant. In addition to teaching, he also set the task of reviving regular concert and opera life, where trained performers could continue their careers and make their music more widely known. Throughout his life, Liszt was able to achieve many of his goals, and he pursued education in this context.

The theme of the exhibition is therefore not limited to Liszt’s work as a piano teacher, but also encompasses a number of broader questions — for example, issues of interpretation, his efforts to expand the teaching repertoire, his musical reinterpretations of other composers’ works as preserved in his instructive editions, and his suggestions for improving certain sections in the compositions of others. In the discussion of the themes of piano teaching, we gain an insight into his individual technical solutions, as we do through the fascinating musical examples of the Technische Studien, in which he summarised his ambitions in this direction, and, through a specific, less well-known example, his openness to the initiatives of the new schools of his time. Among the most valuable written sources from the period are Liszt's letters, sketchbooks, music scores, diary entries and reminiscences by contemporaries and pupils, and surviving recordings of his pupils. We know from Madame Boissier's diary that Liszt taught his daughter Valerie as early as 1832, not only by listening to her playing, but also by drawing her attention to the importance of literature, poetry, music history and philosophy, and by reading excerpts from the works of Blaise Pascal and Victor Hugo. In the last two years of his life, his pupil, August Stradal wrote about a very interesting analogy of Liszt's teaching method: his master taught freely, without any academic constraints, like the Greek philosophers. Stradal compares Liszt's teaching method to that of Socrates, and then mentions Michelangelo, who also allowed his pupils to observe him creating, and they improved their own works as its result. Liszt tried to present to his students an ideal of an artist that he had a lifelong ambition to follow, and which he described in his characterisation of the famous singer of his time, Pauline Viardot: he respected in her a cosmopolitan, her open mind, her talent for different languages, an openness to the methods of different schools of singing and their synthesis. He appreciated her general high culture, her refined style, her elegant behaviour. Liszt, as far as he was able, guided his pupils in this direction, which is why his intellectual legacy remains so influential to our days, too.

Budapest, 25 June 2023.

Dr. Zsuzsanna Domokos

The exhibition was co-organised by the Liszt Museum and the Cervantes Institute Budapest.

We thank the Liszt Museum Foundation and the Péter Horváth Stiftung for their support.