About Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt

1811–1886

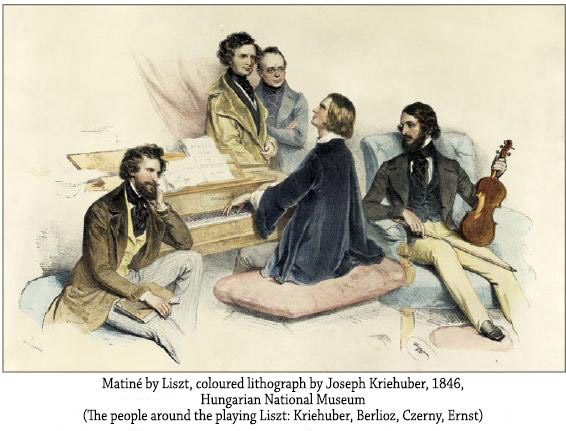

When Liszt first returned to Hungary as a mature artist in 1839–40, he made his debut as a conductor in Pest and Pozsony. With the income of his enthusiastically received concerts, he supported the cause of the Hungarian national theatre and a music conservatory to be established in Pest. He was received as a symbol of the highest strivings of the Hungarian nation. One of the leading Hungarian poets of the time, Mihály Vörösmarty wrote an ode to Liszt, which is a plea to Liszt to rouse his compatriots from "the centuries-long trouble, our history and sins, the weight of which is burdening us".

In 1844, Marie d’Agoult broke with Liszt; the children were entrusted to Liszt’s mother and to various governesses while the composer continued his concert tours, providing his family with financial security. While in Kiev in February 1847, he met Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein, née Iwanowska (1819–87). At this point in his life, Liszt was yearning for peace and stability in order to devote himself to composing. This finally became possible thanks to an offer from Weimar, the residence of a small German Grand Duchy with an important cultural and artistic tradition. Liszt had held the title of Kapellmeister in Extraordinary there since 1842, and finally settled in the city in 1848, giving up the life of an itinerant virtuoso for good. The extremely wealthy, highly educated and independent Carolyne was separated from her husband whom she had been forced to marry at the age of seventeen. She sincerely believed in Liszt’s talent as a composer, and did everything to help him in his work. With her ten-year-old daughter, she followed Liszt to Weimar in 1848 and became his second life companion. A deeply religious woman, she fought persistently for many years to have her marriage annulled so she could marry Liszt. In the meantime she made a home for him in the villa Altenburg, which, despite its name (Altenburg = Old Castle), soon became a meeting place for innovative artists fighting against philistinism. In this "New Weimar”, talented disciples like Hans von Bülow (later Liszt’s son-in-law), Hans von Bronsart, William Mason, Alexander Winterberger, Carl Klindworth, Carl Tausig, Antal Siposs and others received generous help from Liszt in launching their careers.

In Weimar, Liszt strove to turn the city of Goethe and Schiller into a centre of high art once again, after decades of decline, and into a musical centre in particular. As the music director of the court orchestra, he cultivated the classical repertoire, and Beethoven’s music in particular; yet he also provided a forum for deserving contemporary works both in the concert hall and on the operatic stage. He performed operas and symphonic works by Schumann, Berlioz, Wagner, Meyerbeer, Verdi, Flotow, Raff, Rubinstein and Cornelius. Of special importance was his moral and financial support of Richard Wagner, who had been exiled from Germany because of his revolutionary activities in 1848. Liszt recognised Wagner for the epoch-making genius he was; after a successful performance of Tannhäuser in 1849, he mounted the world premiere of Lohengrin the following year. He also programmed The Flying Dutchman and Rienzi, and published several essays to prepare the ground for Weimar as a possible site of the grandiose project of The Ring of the Nibelung.

The Weimar years also saw great progress in Liszt’s own development as a composer as well. This was the time when he was able to finalise and publish several piano cycles that had long been in the making (some of them had already been printed in preliminary versions). These include the Transcendental Etudes, the Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, the Consolations, 15 of the Hungarian Rhapsodies, and the first two volumes of Années de pèlerinage (Switzerland and Italy, the latter including the grandiose Dante Sonata). In addition to a number of significant solo works for piano or organ (such as Scherzo and March or Ad nos, ad salutarem undam), he composed, during this period, his Sonata in B minor, a work entirely novel in both form and content and one of the towering masterpieces in the 19th-century piano repertoire.

Liszt had written for orchestra before (for instance, the 1845 Cantata for the unveiling of Beethoven’s statue in Bonn), and it is not true that his assistants August Conradi and Joachim Raff had to teach him to orchestrate early in the Weimar period. There is no doubt, however, that he concentrated on symphonic music for the first time during those years. Thanks to regular work with his orchestra, his instrumentation became more refined; he was now able to take the next step in orchestral music, moving on from Beethoven. With his programmatic works in one movement, the twelve symphonic poems (including Tasso, Mazeppa, Les Préludes, Orpheus, Prometheus), he created a new genre. In addition to the titles, he often wrote prefaces to his scores to clarify the literary or artistic programmes underlying the works. Following Berlioz’s example, he also composed two large-scale, multi-movement programme symphonies (Faust and Dante Symphonies); both introduce a chorus at the conclusion. His two best-known piano concertos, No. 1 in E-flat major and No. 2 in A major, received their final forms in Weimar as well.

In the field of sacred music, he created an outstanding masterpiece with the Missa solennis (Gran Mass), a festive mass with large orchestra written for the consecration of the Esztergom (Gran) Basilica on 31 August, 1856. Liszt spent five weeks in Hungary to rehearse the Gran Mass, conducting several performances of the work. During the same period, his Mass, for male voices with organ accompaniment was performed at the inauguration of the Hermina Chapel in Pest. At an orchestral concert, Liszt conducted his symphonic poems Hungaria and Les Préludes, which were received enthusiastically by the Hungarian audience. Having had a close relationship with the Franciscans of Pest since his childhood, he now requested admission to their tertiary order. During his next visit home two years later for repeat performances of the Gran Mass, he received the official document attesting that he had been made a confrater of the Fransciscans.

It was not only in Hungary that Liszt appeared as a guest conductor. He gave concerts of his own works in many cities; in addition, he received invitations to music festivals in Ballenstedt, Karlsruhe and Aachen. At these events, he often programmed less frequently played works by the classics, in addition to deserving new compositions. Due to his economical conducting ("We are helmsmen, not oarsmen!”), his unconventional programmes, his support of Wagner and Berlioz, his own innovative compositions and the militant young representatives of the New German School who rallied around him, he became the target of uncomprehending attacks by more conservative musicians. In a press declaration published in 1860, Brahms, Joachim and some other renowned musicians mockingly referred to the music of Liszt and his circle as Zukunftsmusik and would have none of it.

By the late 1850s, Liszt saw that his ambitious plans to bring about a new golden age in Weimar, with himself and Wagner as the leading spirits, were being "thwarted by the pettyness of certain local aspects as well as local and outside jealousy.” He gave up his work as an opera conductor and gradually withdrew from public musical life in Weimar. His interest increasingly turned towards sacred music; he started working on his oratorio The Legend of St. Elizabeth. Taking stock of his past work, he arranged many earlier songs and men’s choruses into cycles, and prepared them for publication. In 1861, he appeared at the music festival in Weimar that marked the creation of the General German Music Association (Allgemeiner Deutscher Musikverein), an organization he had helped found. (He was to remain supportive of the work of this Association to the end of his life, and appeared frequently at their festivals arranged in a different city each year). Soon afterwards, he followed Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein, who had earlier left for Rome. Their wedding, already scheduled, was prevented by vile intrigues. They both remained in Rome, but they gave up the idea of marriage and no longer lived together.

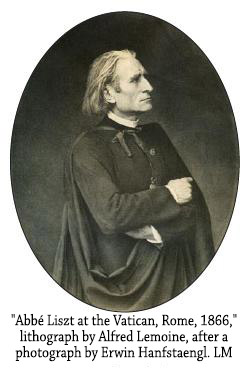

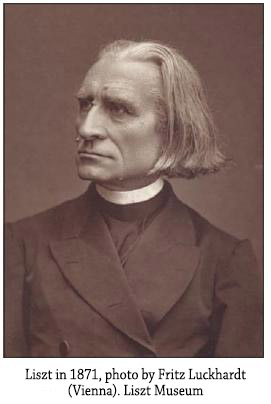

During this new, quieter phase of his life, when he frequently stayed in simple monastic quarters, Liszt was able to complete his St. Elizabeth oratorio, his two St. Francis legends (in versions for piano as well as orchestra), and started work on The Canticle of the Sun and the Christus oratorio. Of instrumental works, he composed his two Concert Etudes (Forest Murmurs and Dance of the Gnomes) and his Mephisto Waltz No. 1 (which is the piano version of the second movement from Two Episodes from Lenau’s Faust). The Totentanz (Danse macabre), composed earlier for piano and orchestra – a paraphrase of the Gregorian Dies irae – was also premiered and published at this time. Liszt had long been interested in the reform of Catholic church music; this now became a primary preoccupation, and he would have liked to play a major role in the implementation of that reform. He was encouraged by Pope Pius IX, who paid him a visit at his lodgings, listened to his piano playing and called him "my dear Palestrina.” Liszt made a thorough study of Gregorian chant and the sacred polyphony of the 16th century to which the reformers wished to return. He strove to deepen his knowledge of religion and, after a period of serious preparation, took the four Minor Orders of the Catholic Church which carried some religious duties and qualified him to perform certain smaller liturgical services. He would have liked to become a choirmaster in the Vatican, but he did not wish to become ordained as a priest, although he always wore a cassock and was addressed as "Abbé Liszt.”

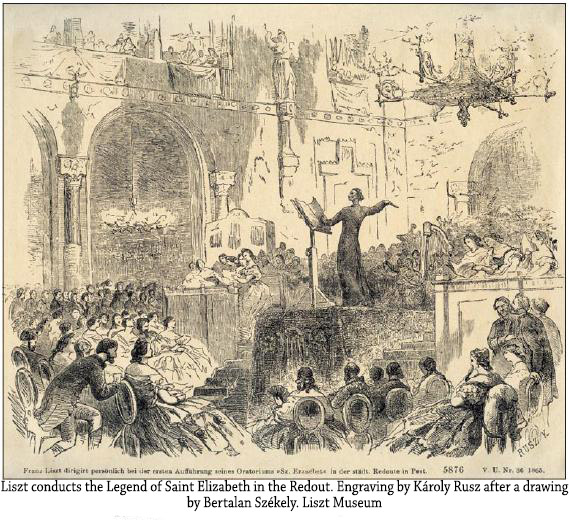

"Abbé Liszt” made his first public appearance in Hungary in August 1865, at the 25-year jubilee festivities of the National Conservatory. He had been instrumental in launching this institution making major monetary donations in 1840 and again in 1846; now he offered his new oratorio, The Legend of St. Elizabeth, as a gift. The work, written on a German text, had originally been intended for performance at the Wartburg (in the Grand Duchy of Weimar) where the Saint, a Hungarian king’s daughter, had lived. In the event, however, the first performance took place at the Redoute in Pest on 15 August, 1865, sung in Kornél Ábrányi’s Hungarian translation. Due to the great success, Liszt conducted a second performance, and regaled his compatriots with his piano playing at a benefit concert where he was joined on stage by Hans von Bülow and Ede Reményi. (After abandoning his virtuoso career, he only played the piano in public at benefit concerts. He was known for being always ready to help those in need and for supporting worthy artistic causes.)

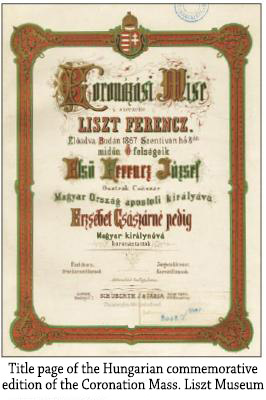

Following the 1867 Compromise between Austria and Hungary, Liszt composed a festive mass. Yet it took concerted action on the part of Hungarian musicians and public figures, as well as the personal intervention of the Empress Elizabeth, to have his "Hungarian Coronation” Mass performed, (instead of a work by a Viennese court composer), at the coronation of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph and Empress Elizabeth as King and Queen of Hungary, at the Church of Our Lady (Matthias Church) in Buda on 8 June 1867. The performers were from Vienna, and Liszt was only present as a member of the audience in the gallery. It was only two years later that Liszt was able to conduct his Mass in Pest with Hungarian musicians and Ede Reményi was finally able to play the violin solos that had been intended for him from the start.

Liszt had suffered several major family tragedies by this time. His son Daniel died in 1859, his daughter Blandine in 1862, his mother in 1866. In 1868, his daughter Cosima left Bülow for Wagner. Having failed to secure the ecclesiastical position he had hoped for in Rome, he accepted the invitation of Grand Duke Carl Alexander of Weimar in 1869 to spend a few months of each year in the Grand Duchy without any obligations whatsoever. In the Hofgärtnerei – the court gardener’s house, a small two-storey villa was at his disposal – he was once again at the centre of a vibrant musical life, surrounded by faithful disciples. It was the beginning of what he called his „trifurcated life,” divided between Weimar, Rome and Pest (Budapest after 1873). During his Roman sojourns, he was a frequent guest of Cardinal Gustav Hohenlohe at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, outside the city. He continued to undertake smaller trips to attend musical events, and sometimes accepted personal invitations as well. His native land came to play an increasingly important role in his wanderings. In 1870, he spent a total of almost nine months in Hungary, some of them at the Szekszárd estate of his closest Hungarian friend, Baron Antal Augusz, whom he had visited earlier too. He conducted at the festive concert commemorating the centennial of Beethoven’s birth and organized a series of matinées at the Inner City Presbitery at Pest, where he also lodged until he rented his own apartment in Nádor Street in 1871. The Hungarian press made noises about his permanent relocation to Pest, and his name was linked to the plans for a new national Academy of Music, which was meant to make musical education at the highest level available in Hungary – under the master’s spiritual guidance.

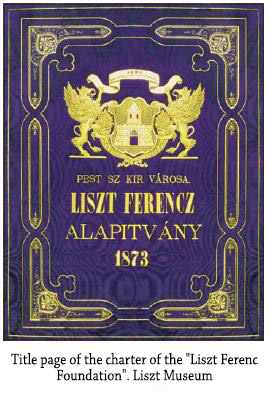

In 1871, he was appointed a Royal Councellor with an annual stipend of 4000 Florins, and while this appointment carried no official obligations, Liszt became even more active on behalf of the new Academy. As he wrote to Augusz on 7 May, 1873: "Please allow me that, apart from my regrettable ignorance of the Hungarian language, I remain Hungarian in my heart and soul from birth to the grave; consequently, I ernestly wish to further the cause of Hungarian music culture.” His ties to Hungary were further strengthened by the great love shown him at the celebration of his 50-year artistic jubilee in Budapest, in November 1873. On this occasion, his sacred magnum opus, the oratorio Christus, was conducted (for the first time without cuts) by Hans Richter, the Hungarian-born conductor who would soon achieve world fame. Henrik Gobbi composed a festive Liszt cantata, and the city of Budapest instituted a fellowship in Liszt’s honour. In token of his gratitude, Liszt donated some of the most beautiful mementoes of his artictic career to the Hungarian National Museum.

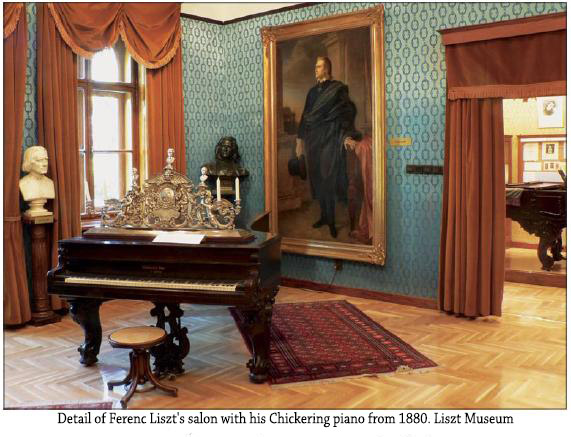

After much adversity, the Royal Hungarian Academy of Music opened its doors on 14 November 1875 on a much more modest scale than originally envisaged. Liszt was named President, Ferenc Erkel served as Director, Kornél Ábrányi as General Secretary; Robert Volkmann and Sándor Nikolits were on the faculty. Erkel’s selfless and indefatigable work, combined with Liszt’s international standing, helped the new institution overcome its initial difficulties. The number of students and departments grew steadily. In 1879, the Academy moved from its initial rented premises on Hal (Fish) Square to a much larger building on Sugár (Radial) Avenue (the present "Old Academy of Music” at the corner of Andrássy Avenue and Vörösmarty Street). Liszt taught his Hungarian and foreign students free of charge in his service apartment as he did in Weimar, offering group sessions, similarly to today’s "masterclasses”. His last Budapest apartment is now the Liszt Ferenc Memorial Museum and Research Centre, which houses his collection of instruments, bequeathed to the Academy, as well as his library of books and scores.

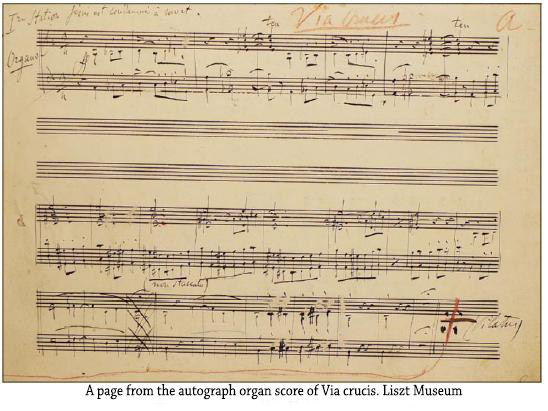

During the period of the "trifurcated life” the style of Liszt’s piano music became spare in its simplicity pointing at the same time to the future to an increasing degree. The journey in volume 3 of Années de pèlerinage, which has no subtitle, was an inner, spiritual one. This cycle, written mostly in the 1870s though not published until 1883, contains laments (The Cypresses of the Villa d’Este I–II, Sunt lacrymae rerum – in the Hungarian mode) as well as a piece of "water music” anticipating musical impressionism (The Fountains of the Villa d’Este). The latter piece, because of the epigraph taken from the Gospels, also connects to the religious pieces opening and closing the cycle (Angelus, Sursum corda). With its unusual modern sonorities and an almost minimalistic sparseness of means, his sacred music evolved in a direction that the reformers of church music within the Cecilian movement felt unable to follow. Thus several of his sacred works, including Via crucis, a meditation on the Passion, remained unperformed and unpublished in his lifetime.

His piano and chamber works from this period are often austere, mournful, intentionally fragmentary, giving the impression of incompleteness (Nuages gris, Unstern!, La lugubre gondola I–II, R.W. – Venezia, Am Grabe Richard Wagners).

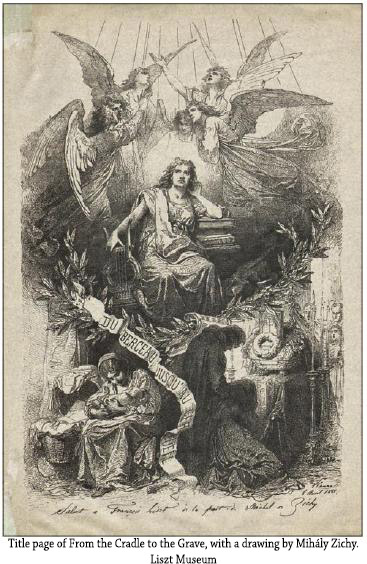

Others show disillusionment or a sense of irony and wit (Mephisto Polka, Mephisto Waltzes 2–4), or indulge in nostalgic retrospection (Elegies 1–2, Romance oubliée, 4 Valses oubliées, Weihnachtsbaum). His late pieces in a Hungarian style (Hungarian Rhapsodies 16–19, 2 Csárdás, Csárdás macabre, Csárdás obstiné, Hungarian Historical Portraits) present musical Hungarianisms that, formerly treated in full-blooded, pianistically effective ways, now appear in stylised form, pared down, and embedded in novel tonal and harmonic structures. ”Is one allowed to write, or listen to, such things?” – he wrote on the margins of the Csárdás macabre, which remained unpublished until 1951. His last symphonic poem, From the Cradle to the Grave inspired by a drawing by Mihály Zichy, likewise ”sublates” the legacy of the great symphonic poems and programme symphonies from the Weimar period. Orchestrated with unusual economy, this piece grew from one movement to three in the course of a lengthy compositional process, and shows, through a web of thematic-motivic interrelationships, that the grave is in fact the cradle of eternal life.

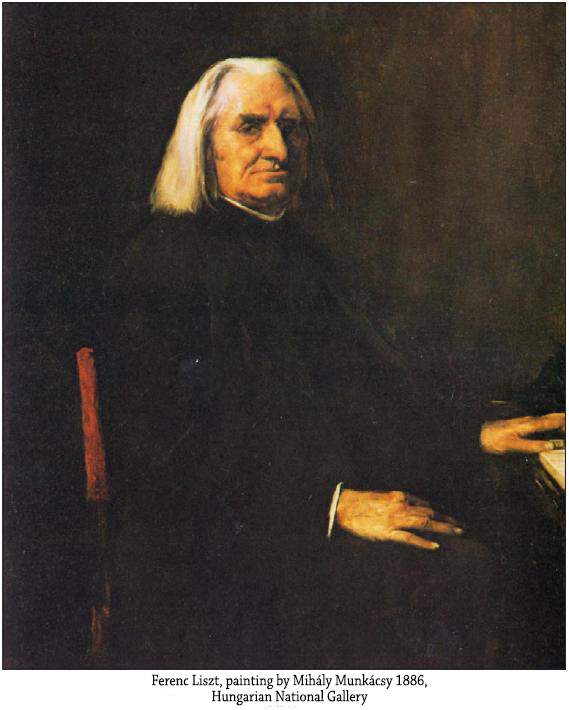

Liszt, now ailing and with deteriorating sight, undertook one final journey to western Europe in response to persistent invitations. His Legend of St. Elizabeth and ”Gran” Mass were performed with great success in Paris and London. Mihály Munkácsy painted his portrait in Paris, and invited him to rest at his château in Colpach, Luxembourg. From there, Liszt travelled to Bayreuth, where his daughter Cosima, a widow since 1883, directed the Wagner Festival by herself for the first time. Liszt arrived on 21 July 1886, already suffering from a severe cold; he developed pneumonia that claimed his life ten days later. Having left behind several contradictory directions as to where he wished to be buried, his daughter finally had him laid to rest in Bayreuth.

During his difficult final years, Liszt had received much support from loving students and friends, from all parts of Europe and even the United States. Several of them (the pianists August Göllerich, Carl Lachmund, Amy Fay, August Stradal, the organist Alexander Wilhelm Gottschalg, the biographer Lina Ramann and others) left valuable descriptions of Liszt’s lessons, his teaching, his views on specific pieces of music. Several Liszt students, both from the Weimar period and from later years, had illustrious careers, including Sophie Menter, Eugen d’Albert, Emil Sauer, Alexander Siloti, Arthur Friedheim, Moritz Rosenthal and Frederick Lamond, and several of them, unlike Liszt himself, lived to make phonograph recordings. The majority carried on the Lisztian tradition as teachers in their own right. His legacy is most alive, perhaps, at the Budapest Academy of Music (now called the Liszt Academy of Music), where Liszt taught from the school’s inception until his death. Two of his most outstanding Hungarian students, István Thomán and Árpád Szendy, became professors of piano there. Ernő Dohnányi and Béla Bartók were both Thomán students, and both became professors at the Academy, too. Together with other students of Thomán and Szendy, they transmitted Liszt’s legacy, which demonstrably lives on to the present day. Liszt’s influence on younger composers was equally important. His encouragement and practical support helped the early careers of Smetana, Saint-Saëns, Grieg and the Russian ”Five”. As Bartók wrote, ”[Liszt] touched upon so many new possibilities in his works, without being able to exhaust them utterly, that he provided an incomparably greater stimulus than Wagner.” May this bicentennial year contribute to making the diverse aspects of his artistic profile and his rich compositional output known even better than before.

Eckhardt Mária

Liszt Ferenc Memorial Museum and Research Centre